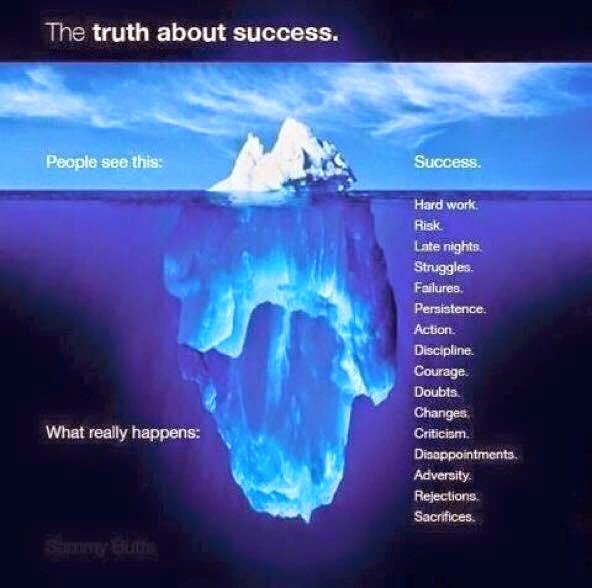

It’s a really common saying – not just in CrossFit, but in life – “Don’t compare yourself to others.” It’s incredibly sound advice, given the vastly differing histories and context that go into each person’s development. Comparing your training to someone else’s will rarely leave you feeling more confident about your progress, in large part because it’s easier to spot someone else’s biggest successes and harder to perceive their struggles, their setbacks, and the other countless inputs that they brought to the table.

It’s a really common saying – not just in CrossFit, but in life – “Don’t compare yourself to others.” It’s incredibly sound advice, given the vastly differing histories and context that go into each person’s development. Comparing your training to someone else’s will rarely leave you feeling more confident about your progress, in large part because it’s easier to spot someone else’s biggest successes and harder to perceive their struggles, their setbacks, and the other countless inputs that they brought to the table.

However, I’ll submit that in certain ways, comparison has helped me to realize that something was not right. In the last six months, I noticed that I had CrossFitting friends ten, twenty years older than me, who were recovering much more quickly from workouts — despite the fact that I was usually eating a recovery-friendly whole food gluten free diet that strategically stacked my starchy carbohydrates with protein just after workouts.

I was diagnosed with hypothyroidism last year. While very low carb diets have been tied to thyroid problems in women, I regularly consumed a moderate and activity-appropriate amount of carbohydrates. I couldn’t help but wonder if there was more to the picture than just lousy workout recovery and hypothyroidism. My doctor began ordering several labs for me to try and get to the bottom of my condition.

Then, this spring, just before going over the umpteenth lab results set with my doctor, a lightbulb flickered on in my head. I asked my primary care physician, an integrative medicine MD, if she thought it was worth testing me for gene mutations on the allele for methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (henceforth MTHFR). The allele critically important because it is the blueprint for MTHFR, an enzyme which adds methyl groups to molecules. The name for this enzyme’s methyl group management is called methylation, and methylation is critically important to a panoply of physiological functions, to include: metabolism and energy recruitment, epigenetics (turning genes “on” and “off”), neurological function (in part because of MTHFR’s impact on neurotransmitters like serotonin) and neurological development, and susceptibility (including stress-related susceptibility) to intestinal inflammation and permeability, to name just a few. As you might guess, since methylation is so critical to these functions, its impairment is tied to a similarly long list of diseases and conditions.

I had seen chatter about MTHFR on Twitter for the last couple of years, usually in relationship to autoimmune conditions and autism spectrum or other neurological conditions. It had dawned on me, though, that since my youngest daughter is on the autism spectrum, she could be a MTHFR mutation carrier (and as it turns out, MTHFR mutations are found much more frequently in autistic kids)…and therefore as her parent, I was likely the carrier of at least one MTHFR mutation, too.

As it turns out, I’m a type of mutation carrier called compound heterozygous. It signifies that I carry one copy each of two different mutations, also known as polymorphisms. My mutations – A1298C and C677T, can together cause more damage than the sum of their individual impacts. My lab report tells me that, “Individuals who are compound heterozygous for the C677T and A1298C alleles, which produces a C677T/A1298C genotype, have according to some studies 40-50{cdc8dacb124d4b27fd7a4c8cb0e89e6e093c68cad0607afd388ff915747d78c2} reduced MTHFR enzyme activity in vitro and a biochemcial profile similar to that seen among C677T homozygotes with increased homocysteine levels and decreased folate levels.” In other words, having one of each of those mutations hampers my MTHFR enzyme activity about as much as those with two copies (homozygous) of the most significant MTHFR mutation, C677T.

This lab work suddenly helped so much lock into place. Many of my suspicions finally had basis in reality. No wonder my recoveries were not lining up with my CrossFitting friends’; my genes meant I could possibly be clearing lactic acid from my muscles at roughly half the normal rate. Beside that relatively mundane inconvenience, I now must work with my doctor to measure and address homocysteine levels in my blood and my risk for several MTHFR-mutation-associated diseases – not just by considering targeted supplementation, but also by using a multi-pronged approach that includes my microbiome/gut health, stress, sleep, cortisol levels, and other aspects foundational to my physical and mental heath. Although I doubt the journey through MTHFR mutation management will be linear, I’m looking forward to testing, retesting, and continued coordination with my health care providers to address my body’s needs.

Do you have an MTHFR mutation? How did you begin to tackle your body’s unique needs?

~

SOURCE: Primal Kitchen: A Family Grokumentary – Read entire story here.