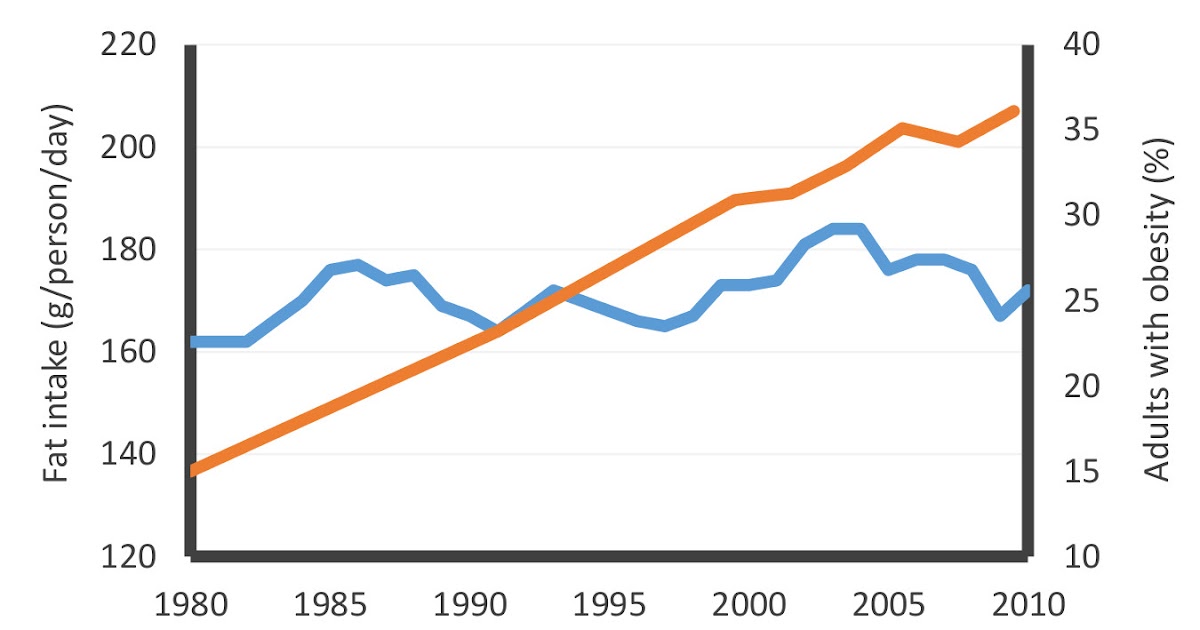

In this post, let’s look at another putative driver of obesity: our fat intake, and especially our intake of added fats like seed oils, butter, and olive oil. Like the graphs in the last post, the data underlying the following graphs come from USDA food disappearance records (not self-reported), and NHANES survey data (1, 2). Also like the last post, the graph of total fat intake is not adjusted for waste (non-eaten food), while the graph of added fat intake is*. As a consequence, the figures for total carbohydrate and total fat intake are higher than actual intakes, but still good for illustrating trends.

As you can see, there is no real trend here. Our total fat intake increased slightly between 1980 and 2010, but mostly we just bumped around with no real directionality. This does refute the common claim that our fat intake declined over the course of the obesity epidemic. All available data agree that our absolute intake of fat has hardly changed at all. It only declined as a percentage of total calorie intake.

Now, let’s see what happened to added fat. As opposed to the fat naturally found in foods like meat, nuts, eggs, dairy, avocados, and olives, added fats are those that are extracted from foods and concentrated to a nearly pure state. These include seed oils like soybean and canola oil, as well as more traditional fats like butter and lard, although today we eat much more of the former than the latter.

Hmmm. Added fat intake increased by 28 percent over the course of the obesity epidemic, and it’s the only factor out of the four we’ve examined that consistently increased in parallel with our expanding waistlines.

This doesn’t surprise me at all. Here’s why:

- Added fat is the most calorie-dense food on the planet.

- Added fat is one of the most effective ingredients for enhancing food palatability.

- Added fat has a very low satiety value per calorie.

- People eat more total calories when extra fat is added to their food.

- Added fat fattens a variety of non-human species, including mice, rats, dogs, cats, pigs, and monkeys, when added to their food.

The rise of added fats was probably a contributor to the obesity epidemic, along with other diet and lifestyle factors. While fat isn’t necessarily fattening when it’s eaten as part of whole foods with lower calorie density and high fiber or protein (meat, yogurt, avocados, nuts), a lot of research has converged on the conclusion that added fat is fattening.

[Edit 11.23.15: An astute reader pointed out that the absolute increase in total fat and added fat intake are actually about the same, which I confirmed was not just noise by adding best-fit lines to the graphs. This suggests that we simply increased our added fat intake on top of our other sources of fat, rather than replacing one with the other.]

* I did adjust the data for an artifact between 1999 and 2000 that artificially inflates fat intake data after 1999. This was caused by a change in the assessment method for certain types of fats.